The experience of covid-19 shows the need for a more holistic

approach to health security and its closer integration into

urban resilience planning. It is still too early to draw detailed conclusions on

the implications of covid-19 for health security. The pandemic continues at the time of writing. Even

were it over, robust, internationally comparable data on

what has happened are still rare. Nonetheless, the need to

rethink health system preparedness is already clear. This must have several elements. The first is to look

at different kinds of diseases and the wider determinants

of disease as an interrelated whole rather than considering

them in silos. The second is to think of populations as a whole, which will especially involve providing effective care for currently marginalised groups. The

third is to integrate health emergency planning more fully

into urban resilience measures that, often, have focused more on dealing with natural disasters and environmental concerns.

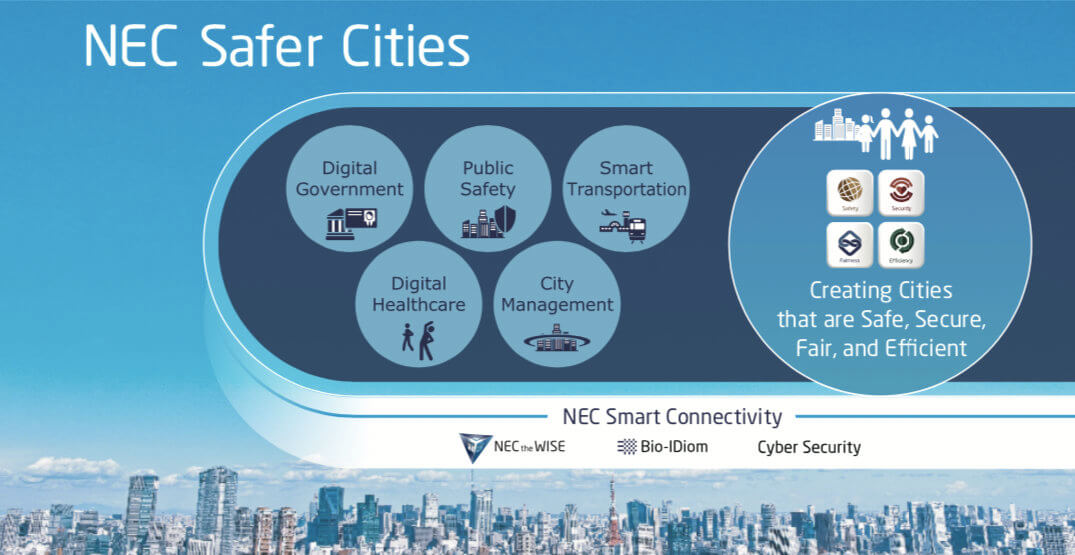

Digital security at the city level is too often insufficient

for current needs and insecurity will multiply as urban areas

increasingly pursue smart city ambitions. The index data show that internet connectivity is becoming

ubiquitous, even in our lower-middle-income cities, and

could be effectively universal within a decade. Meanwhile, 59 of our 60 cities have started the process of becoming a smart city or expressed the ambition.

This makes current levels of digital security worrying. To

cite two examples from our figures, only around a quarter

of urban governments have public-private digital

security partnerships and a similarly small number look at

network security in detail in their smart city plans. Such

data are representative, not exceptional. Gregory Falco –

assistant professor of civil and systems engineering at Johns

Hopkins University– notes that “the digital security of cities is

generally pretty terrible.” Improvement requires rethinking

digital security on several levels: cities must see it as an

investment, or at least an essential insurance policy,

rather than an unproductive cost; they must understand that the

nature of the technology requires a city-wide approach

rather than one fragmented by departmental silos; and,

finally, digital security – and especially protection of

smart city networks – needs to involve providing the level of

safety that citizens expect and demand. Indeed, smart cities need

to be built around what urban residents want, or they will

fail.

Although our index data show little change in various

infrastructure security metrics, experts report that covid-19

has brought this field to a fundamental inflection point. Change in infrastructure can be slow, with decisions sometimes

having repercussions for centuries. Accordingly, certain indicator

results, such as those covering power and rail networks, show

little change. This stability does not reflect the current state

of this field. Covid-19 has brought a level of uncertainty around

the likely demands on urban infrastructure– and therefore how to

keep it secure –which Adie Tomer, leader of the Brookings

Institution’s Metropolitan Infrastructure Initiative, describes as

“nuts compared to just two years ago.” It is unclear the extent to

which lockdown-associated developments will diminish, or

accelerate, when the pandemic ends. Greater levels of working from

home, increased digitalisation of commerce, and growing resident

demands for more sustainable urban communities with services

within walking or cycling reach all have extensive infrastructure

implications. Meanwhile, ongoing urbanisation, especially in Asia

and Africa, mean that the next two decades must be ones of rapid

infrastructure development in order to meet the basic needs of

city residents. This will require a shift to greener

infrastructure and better management of existing assets. Our index

results, though, show that in these areas the majority of cities

will have to raise their game.

Personal security is a matter of social capital and

co-creation. Our index figures show, as elsewhere, that personal

security pillar scores correlate closely with HDI figures for

cities. A closer look yields a less predictable result. A number

of cities, in particular Singapore, seem to combine low levels of

inputs with excellent results in this field, in particular when it

comes to judicial system capacity and crime levels. While most of

the examples of this combination are in Asia, they exist elsewhere

too, as in Toronto and Stockholm. One way that these various

cities can accomplish apparently doing more with less, say our

experts, is higher levels of social capital and cohesion. The

resultant sense of connectedness, shared values, and community

also allows greater co-creation of security with citizens. The

latter not only multiplies the efforts of city authorities to

improve personal security, but it also helps define security in

ways that are more meaningful to residents.

Most cities have strong environmental policies, but now must

deliver results. Unlike other pillars, low- and middle-income cities often

do well on environmental security. Bogota, for example,

comes 4th overall. One explanation is that good environmental

policies are widespread. The increased interest in reaching

carbon neutrality that has accompanied the pandemic

will only strengthen the impetus for still better plans.

The challenge, though, remains implementation. Here, even

higher income cities are lagging noticeably behind their

ambitions. As in other areas, the key to success will be to take

an overarching approach to environmental issues rather than a

fractured one, and for cities to work with residents rather

than seeking to direct them.